Two revelations from yesterday. First, my anonymous friend M (don’t want them to get pestered with inquiries yet) gave me a draft of a novel so delightfully full of cool ideas that I could not reading even as I was driven along a serpentine mountain road. The revelation, apart from the obvious conviction of their genius, was that my stomach could not handle it and I felt like hurling the contents of a fine dinner over the beautiful scenery. Though really I should have known that from experience. Sidepoint: we are watching DEVS nos, which apart from hammering metaphors in with a sledgehammer, is not bad.

Second was that I kept thinking about a friendly interrogation that Stephen Yang of this post conducted on me, asking me to what extent we incorporate the real world experience in abstract science, or whether we are completely removed from it. (I also invited him to Jerusalem almost immediately, looking forward to your visit!)

I had two immediate answers for him: One is indirect, in that nature (in the sense of everything not inside the mind, so maybe the outside world would be a better term), at least for me, acts as cleaning current, flushing out the noise of repetitive thoughts that accumulate in creative thinking by overwhelming the senses.

I also told him a mathematician guild secret: even when we say that we think in purely abstract terms, you have to watch our fingers. What we say is a distraction, and often you can see our hands move when communicating facts all the same. But pssht on that.

And I also had a concrete example of how at one point my PhD advisor Günter Ziegler used an architectural principle going back to Gaudi to construct counterexamples to a conjecture of Legendre.

But that was actually not the first time I had a understood something using such inspiration. When I was a child, I liked to paint with watercolors. Not that I was good at it, it was an unholy mess.

But when one used a little too much water you could drag around the colors on the canvas and still change the result. Of course, that never ended up well, because the further I dragged the color, the worse it became.

Years later I was struggling with differential geometry, and did not get a single point for the most part. I did fine on the exams, but I could not understand what was going on, feeling more like a dancer in the dark that would hit the wall really soon than someone with command over what he was doing. At some point, though, my undergrad advisor handed me a book I cherish to this day, that has kept me awake at night and helped me through hard times.

The satanic bible.

Also, Lectures in Metric Geometry. Though I grew to like Gromov’s somewhat deeper and perhaps more cryptic elaboration on the subject more over the years, the book introduced several concepts that transformed my concept of geometry, in particular the notion of a metric space of metric spaces.

Now, this concept goes back to Hausdorff, and since then, many more similar ideas have popped up. But one can think about it like this: If you have subsets A and B in a metric space X, then one can ask how different these two shapes are (though the question of how much energy it takes to move them leads to another notion that is equally interesting).

that is to say, I look how well A covers B on canvas X and vice versa.

To imagine a metric space of metric spaces is then this: Given two metric spaces X and Y one can embed them into a isometrically into a common world Z, and measure the distance of the images:

But there could be many ways of finding such a larger space, sort of like having two fingerprints and matching them up by trying different positions. The Gromov-Hausdorff distance of the two metric spaces X and Y is then the infimum over all such embeddings:

Once this is established, one can do interesting things on metric spaces, such as study how stable certain subsets of a the space of metric spaces are under flows deforming them.

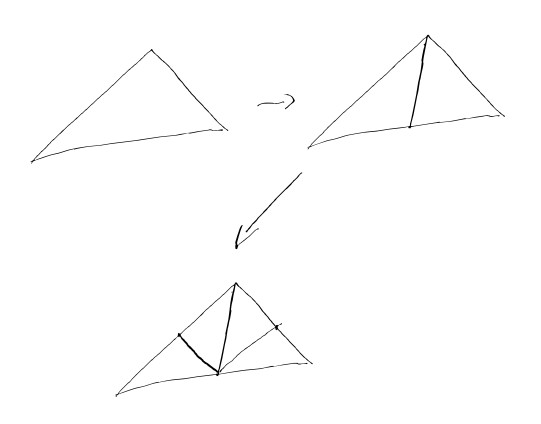

Let me give an example that neatly shows how useful it is to think about moduli spaces of spaces in a geometric way (joint work with Igor Pak). And that example is Rivara bisection.

The motivation arises when a real world person tries to solve a partial differential equation, for instance to understand the stress a load puts on a material, then one method often used is the finite element method: One divides the region into triangles (in dimension two) or simplices (in higher dimension) and solves a combinatorial approximation of the continuous equation.

This of course gets better if the mesh is finer, but there is a caveat: If triangles (or simplices) become very thin, the approximation becomes bad.

One idea to refine the mesh and hope that this does not happen is to just naively take the worst offender, and cut that boy in two. In other words, one takes the longest edge, and cuts it into two parts, and extends that cut to the rest of the simplex. And then, repeat until it is fine enough. This is the Rivara bisection.

Now, one could think that there is no way that this produces worse and worse simplices. It just seems so nice. But that is still unknown in higher dimensions, and an upcoming paper of myself and Igor will discuss just these challenges in higher dimension. But in dimension two, it is known to be true: this process never degenerates triangles, it does not make them flat no matter how long we run it. In fact, up to homothety, only a finite number (depending on the starting triangle) of triangles will ever appear; the process is quasiperiodic.

The proofs, however, feel quite technical to me, so I want to present here one that looks at the moduli space of the simplest metric spaces: the space of discrete metric spaces. Given n+1 points, we could dream of associating distances between any two of them:

This forms a metric space if and only if the Cayley-Menger matrix

is positive semidefinite. This describes the space of all simplices on n+1 vertices. And for n=2, we get the space of triangles.

Notice that we involve only square length, so we can parametrize the moduli space of simplices and triangles by

Notice further that this space is convex: If forms a metric, and

does, then equally so does

.

Lets call this space , and focus on

. The trick is now this: Observe first that there is a starting triangle does not degenerate: take the isosceles triangle with one right angle (and squared edgelengths 1,1, and 2).

Because, up to homothety, the Rivara bisection takes this simplex to itself. We have a stable orbit O.

Now, we convince ourselves that every orbit is stable. We do so by introducing a measure of energy. Consider an element of T. Set

That is the energy of a simplex. Notice that

- the energy is positive, continuous, and invariant under homothety, and

- is smaller the more degenerate the simplex is, and

- the maximizing

associates the longest edge of

to the longest edge of

.

The last point is important, because it implies that the energy of a triangle is non-decreasing under Rivara bisection. And that is it. You understood the geometry of the Rivara bisection. In fact, one can understand it a little better still: Every time the energy increases, it increases by a nontrivial amount that is bounded from below.

Hence, the energy can only increase a finite number of times. Hence, we also obtain a fine bound on the number of homothety types we ever can see, in terms of the energy.

Final thesis: The best way to get into your shoes was invented by Michael Jackson.