I have some postdoc/student positions available. Just contact me and we can chat about science.

There is also the FSMP you might want to consider.

I have some postdoc/student positions available. Just contact me and we can chat about science.

There is also the FSMP you might want to consider.

Recently, we got back several referee reports for this paper here which were quite positive (well, the comments were “the construction is genius and it works, but the exposition is quite messy”; I choose to take it as a compliment), which made me very happy because it is a very classical conjecture with some nice implications. And seeing people who took their time to understand the construction (and wade through my horrible writing, because the “messy” is certainly my fault) made me quite proud…

Speaking of, though, classical conjecture…. well one part was Oda’s. That was fine. The other conjecture we solved was “Alexander’s conjecture”, named after James Waddell Alexander. Everyone kept calling it that, and Alexander certainly worked on related problems and proved something weaker in a 1930 paper (building on work of Max Newman, who, another cool fact, is best known for becoming a codebreaker later).

Next year we will have another combinatorics and geometry conference in Greece, organized with Enis Kaya, Evita Nestoridi, Stavros Papadakis, Vasiliki Petrotou and Christos Tatakis. Looking forward to seeing you there!

AI claims of achievement at the IMO aside, I found this really cool: One of the gold medalists (from China) won gold despite cerebral palsy

With Tosun, Mineev, and Tatakis. See you there 🙂

Firstly, for a while now, Harald Helfgott, Vasiliki Petrotou, Arina Voorhaar and myself have been organizing CAGe, a bimonthly (the bimonthly that happens roughly every 6 weeks) miniworkshop at IMJ in Paris. The idea was to have this instead of a seminar so that the visiting speakers could also have interesting talks to join, and so that there would be more of a theme each time. Next time is March 4, with Evita Nestoridi, Carsten Peterson and Jacinta Torres. Enjoy and join!

Secondly, after settling down at IMJ and getting a couch and carpet for my office, I will be teaching a course with Harald in the spring, on spectral graph theory. Find it here.

Wanna hear a cool thing we realized while exploring lattice polytopes, but that took us much further?

So you know how in a smooth manifold, we can think of the fundamental class by integration over the manifold; that’s just de Rham cohomology of course, and we come to think of the fundamental class as something related to volumes and measures. This beautiful picture is something very geometric, in the end, one might think.

Continue readingI want to say a word about a theorem of Bing, and a consequence I am sure he knew, and I thought everyone knew, so I just assumed it often in talks and papers (I do this often, unfortunately).

I did this several times, until a prominent mathematician said, during a colloquium in Paris, angrily that this could not be true. So maybe it is less folklore than I thought.

Anyway, to the theorem: Bing proved that if a simplicial complex X embeds facewise linearly into a PL manifold M, then M has a triangulation that contains X as a subcomplex. That seems believable, and is not so hard to prove, and contained in R. H. Bing, The geometric topology of 3-manifolds, AMS, 1983.

Now the corollary that people have problems with is this: If X embeds piecewise linearly into a PL manifold M, then M has a triangulation that contains X as a subcomplex.

That is a bit counterintuitive, as the map may be rather wild, and locally not flat. In fact, the theorem requires that we deform the map a little. But it is true nevertheless, and it is what Zuzana Patáková and I proved.

One of the fundamental results of PL topology on one hand, and the algebraic geometry of toric varieties on the other, is that any map in the respective categories (PL homeomorphism on the one hand, and birational map on the other) can be factorized into elementary moves: A PL topologist would call these stellar subdivisions, the operation of picking a point in a simplex of the polyhedron, and forcefully subdividing it by coning over the boundary of its neighborhood. And their inverses.

An algebraic geometer knows these operations as blowups and blowdowns.

Unfortunately, the result is quite messy. One has to go up and down a lot, alternating between both operations.

For this reason, two of the pioneers of the respective areas, Tadao Oda and James Alexander, asked independently whether one can simplify the zig and zag of these operations: Is it true that we can put all stellar subdivisions/blowups first, and only then do the inverses/blowdowns.

In other words, is there a common stellar refinement of both? To me, this question always held fascination due to its simplicity. More than that, however, it was introduced to me by a dear friend, Frank Lutz, who passed away recently. I will write a bit more on the subject in the next days. In the meantime, you can grab the preprint here.

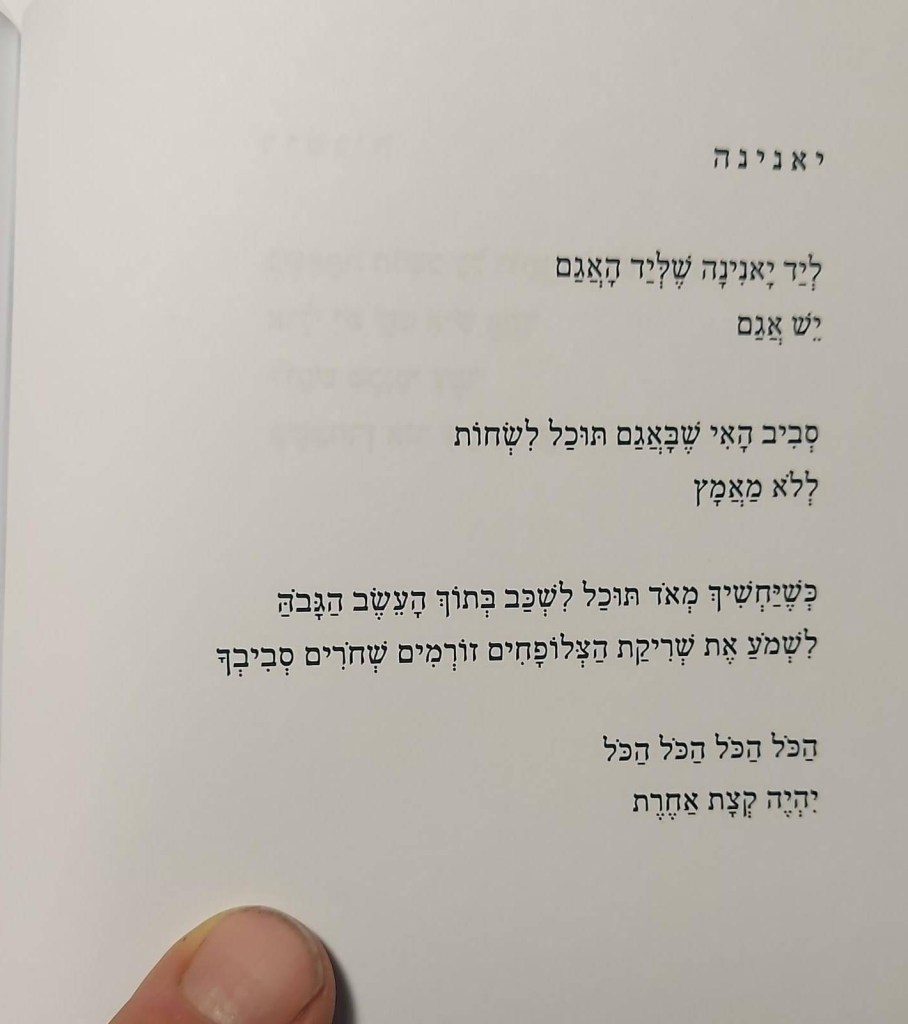

Anargyros Katsampekis, Stavros Papadakis, Vasiliki Petrotou and I organize a workshop in beautiful Ioannina next year, details can be found here.

Also, lecture series in Miami with Stavros Papadakis and Vasiliki Petrotou at IMSA.

site of the metric2011 program of Centre Emile Borel

"Marge, I agree with you - in theory. In theory, communism works. In theory." -- Homer Simpson

Chasing dreams from mathematics to the real world

Homepage / Math Blog

Math, Madison, food, the Orioles, books, my kids.

Because "exact science is not always exact science."

always busy counting, doubting every figured guess . . .

a personal view of the theory of computation

un regard personnel sur le monde extérieur

Views on life and math